Westward through Hell

Summer of 1966, somewhere on Interstate 8 between Gila Bend and Yuma. I’m in the back seat of my father’s black Dodge 330 4-door sedan. The faithful, ugly car has carried us west across the country on the burgeoning Interstate Highway System four times, but there’s no return trip planned today. The destination is not a vacation. We are cruising to a new home, my father at the wheel, as always, piloting us to a concrete destination that he dreamed up in his imagination, with my mother’s agreement.

The air conditioning is failing. There’s a trace of frigid air emanating from the front vents, but not much. It’s 104 degrees outside. I touch the warm glass of the window. Mom wants to stop and give us water. Dad says no. Maybe he thinks the car will heat up too much and that we will all be baked alive before we get to Araz Junction and the bridge into California that crosses what’s left of the Colorado. The river is dammed six times south of Hoover. I’m cooked already and feel damned as well.

There’s water in the trunk of the car, but instead of fighting with Dad over a short halt, Mom hands out cans of unrefrigerated orange soda to us—the only liquid she has in the car at the moment. Lukewarm, sugared, vile—I drink it down like a parched sailor in a lifeboat on a salty sea. Immediately I want to throw up, but I don’t. I’d rather die. Dad would be sympathetic, but then I’d hear it as a tale told to his friends to embarrass me for years. No way will I let that happen.

As we speed down the brand-new interstate the road passes through a cattle ranch stretching to the horizon on either side of the road and into the distance ahead of us—a brownish ocean of undulating livestock. The reek of cow shit and my own fear enters my nose. I am breathing thickness and sickness. My head is spinning.

“Oh my God,” my mother says. “What a stench. Stinking old cows.” She waves her hand in front of her face as if shooing away a cloud of invisible flies. My mother never uses the name of the Lord in vain, something my father monitors in his children’s speech—something I am careful to avoid. Dad remains silent.

I am fed up with all this travel, weary of being cooped up in the back of the car—three days now. We are in a hurry and not stopping to see the sights. I already miss my Pittsburgh pals. I’ll never see them again. I hate everything.

Then my father turns around and leers. His wayward eyebrows bristle. He’s going to say something he thinks is funny, I can tell.

“This is what hell is like!” he says, and turns back to watching the road. All that’s missing is the “bwa-ha-ha.”

One Year in San Diego

Sun and Mexican food. Bicycles at last. Long road trips to watch the sun rise over the Anza Borrego desert. No more snow. Shorts in the winter. Picnics. More Catholic school—School of the Madeleine on Illion Street. Brown uniforms for the boys: short sleeves for First through Seventh grade, long sleeves and black ties for eighth graders. Plain plaid skirts for the girls. We arrive in late summer of 1966, and the local stores are all sold out of long-sleeved shirts. I receive a dispensation for my bare forearms, yet still wear the tie, which creates a rumor that I am really a Seventh grader who has advanced because of his academic qualifications. This marks me as an outsider. I am treated as such by my peers. I flunk math, but not intentionally.

The church is on the side of a mesa—a view of Mission Bay, the vista like something from the utopian science-fiction novels I love. Years later I look at it again through the reverse memory telescope—so tiny, so ordinary. But the Pacific Ocean and the edge of the continent is right there before me, and the desert and my father’s Edward Abbey dreams are not far from home. Daytime road trips on the weekend. Burgers on the grill. Family times.

A rental house on Cowley Way where I can hear the neighbors drinking and fighting at night. My closest friends are outcasts like me—now nameless, I cherish them. There are guitars in the house. My father is unhappy, beleaguered by his boss, a stupid man named Carl, whose girlfriend is English and sweet. Carl owns a yacht. On random Sundays we steam around Mission Bay in a cloud of diesel exhaust, a brief excitement. A day trip to Ensenada, Mexico, before the borders became impregnable without passports. Another to Tecate, where my guitars originate.

Our roots never take hold in that cultural soil, save for cuisine. Tacos and tostadas, not just from taquerias—a recipe from Sunset magazine that my brother still occasionally rustles up in my kitchen. Food that always leads to the redemptive chant today: “Thanks Dad and Mom…” Can they hear us on the other side? After a year we scurry north. To Oxnard.

Oxnard. A name right out of the Firesign Theatre’s “Funny Names Club of America,” christened by the town’s founder, Henry, who built a sugar beet processing plant there in 1897. Frustrated because bureaucrats couldn’t determine why Henry wanted to name the town after the Greek word for sugar, zachari, he named it after his family. Civic debates over changing the name ensue repeatedly.

Field of Beans

A brand-new tract house in the middle of lima bean fields—the local ranch family is selling off the family agricultural estate to developers. I can see over the back fence and watch the harvesting—bulky, rumbling machines running all day and night that keep me awake. Another steampunk sci-fi vision.

As months and years pass more homes are excreted onto the rich soil that have been fertilized for decades with chicken shit. Advantageous for gardening. My parents plant citrus trees, cacti, and succulents. I can still hear neighbors fighting—it seems that California is filled with unhappiness. I keep to myself. My brothers play ball in the suburban streets.

My dad never wears tennis shoes—in their place leather Oxfords tied with thin shoestrings, black socks that fall down around his thin ankles, revealing his pallid skin. Thankfully he never wears shorts. My mother, patiently silent, puts up with my father’s crazy schemes.

“If you don’t have anything good to say about someone don’t say anything,” she teaches me. It seems wise then. I know it is now.

In August 1967 there is a day when Dad registers me at the local Catholic high school, not long after we move into the new house. We sit in the principal’s office. Behind the desk a priest, Monsignor Joseph Pekarcik, ex-Marine. Wire-rimmed glasses. Stern gaze. No grin. Curled grey hair like soap-scour pads. Next to me my father, a patriarchal smirk on his face. As they engage in autocratic small talk, I sit in a chair feeling unimportant and diminutive, as if I am being reduced in size due to the power of the invisible super-vision shrink ray transmitting from the priest’s totalitarian eyes. I think that if he smiles his cheeks will crack and his face might fall off. Wisely, I keep my mouth shut, rebelling internally.

He says to my father, “Mister Gill, how do you supervise your family?”

“It’s a benevolent dictatorship.” My father responds as if they are old friends sharing a secret handshake and winking at one another. I wonder what Mom would say if she heard that—she’d laugh in his face and require that he make his own dinner.

Monsignor Pekarcik nods approvingly and scrutinizes me again. He knows he’ll have no problem with me. I spend four years avoiding him while he catches genuine miscreants, sneaking up behind them while wearing thick-soled silent shoes, curtailing their felonies—violations of the dress code. “The heels on those boots are too high, Mister, and those pants are too tight. Go home and change them. Now.”

Once again I don’t know anyone on the first day of my freshman year. Two parishes feed eighth graders into the high school. Everyone is confused—I seem to have come from some other country or planet. Yet in a few days I realize my family will remain here in this agricultural town for an extended time as it transforms to a Los Angeles bedroom community. The outlandishly named city becomes my first hometown, despite the crop dusters buzzing around the neighborhood. Here I make lifelong friends—not nameless and forgotten, still with me fifty years later: John, Tony, Marie.

I become a high school scholar, the pampered eldest Catholic boy—both my siblings are enrolled in public schools. My parents never speak to me about money. They never give me much of it either, but once again we seem flush. My dad finds a job in a camera store, builds a business selling high-end stereo gear and classical audiophile LP’s. Eventually my mother works as a secretary. I find baby-sitting jobs in the neighborhood for paperback book money.

Riding my bike to the public library is unalloyed joy. Freedom in the stacks as I search out science-fiction, dreams of future cities in my head—domed or doomed. Asimov, Clark, Bradbury—Heinlein not so much. Mystery and detective novels. World War 2 naval history. My father subscribes to Road and Track. I devour every issue, following Formula One in Europe, while helping him rebuild Alfa Romeo sports cars in the garage.

On weekends, road trips to Pine Mountain and Reyes Peak in the Los Padres National Forest. Racing down the long straightaway of Gonzales Road, my father behind the wheel. “Don’t you dare ever drive like this,” he says—while driving like that.

At the end of Gonzales Road, the Pacific Ocean and the edge of the continent. The smell of the sea. Occasional fog. On clear nights, stars. Sometimes, sporadic explosions of aborted rocket launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base 100 miles up the coast—the vapor from the blasts hanging like florescent blossoms, unfurling smoke and fire across the setting sun. C-5 Super Galaxy cargo jets rumble and roll over the house on final approach to Oxnard Air Force Base.

In 1969 men land on the moon. My father scoffs, I’m not sure why. I have nothing good to say to him about his cynicism, so I ignore him. One year earlier America burns. Martin Luther King is assassinated. In June I listen to Robert Kennedy speak after winning the California Democratic primary. Then another shot from a gun while the harvesters churn more lima beans from the ground and houses grow in the fields overnight.

In the background of all of it my transistor radio and radio station KBBY—Beatles, Beach Boys, The Who, Jethro Tull, Led Zeppelin. All surreptitiously received through a small earpiece. I am in a safe zone—protected, loved, nurtured—even though the country is falling apart, and thousands of soldiers are dying in a pointless war in Southeast Asia.

My father tells me I’m going to college. Sounds good to me. Has to be a Catholic College though. I apply to Loyola in Los Angeles, Santa Clara in Santa Clara, and a small liberal arts college in Moraga—Saint Mary’s College of California. I am accepted at all three. Dad and Mom arrange for tuition, and I help out with a small scholarship from the State of California.

January 1971. Dad and I travel north to Moraga to see the campus. A rainy, foggy day. The place seems like something out of my own moist, murky, romantic dreams—redwood trees, owls, rain, and…coeds. I adore it, and it’s as far away from my dad as I can get.

Looking at the Channel Islands with Chris

In My Mother’s Kitchen

Watching TV with Chris and Paul

A Festival of Nerds

John and Me

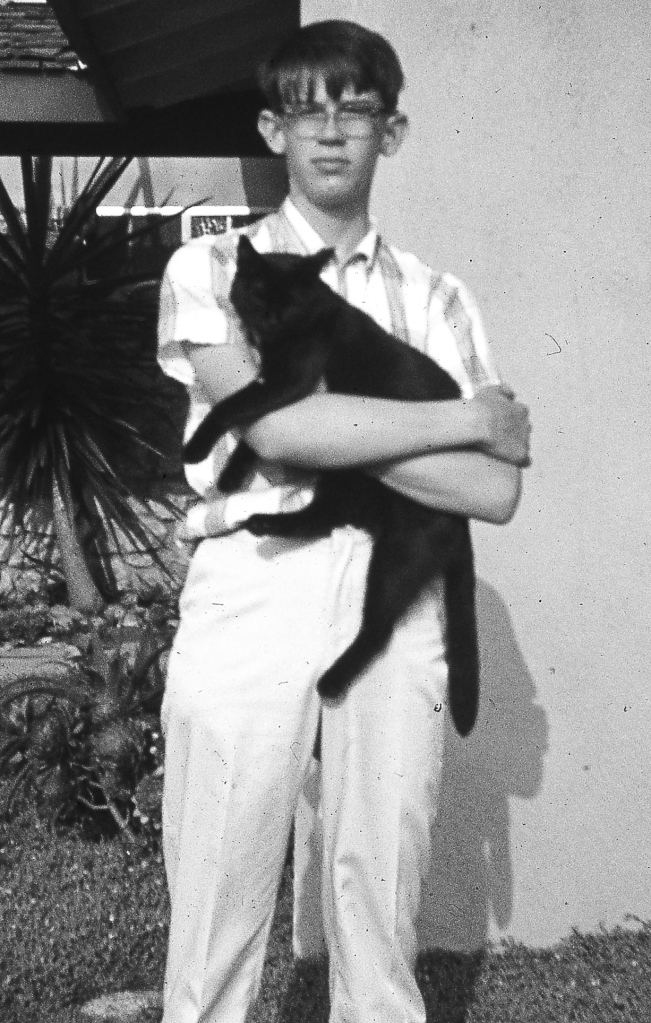

“This is my cat and you can’t have him.”

The imagination should be allowed a certain freedom to browse around.

Thomas Merton, Contemplation in a World of Action

This is truly wonderful writing! I particularly loved turns of phrases like “The river is dammed six times south of Hoover. I’m cooked already and feel damned as well.”

LikeLike

Thanks. Good to know that it works for you.

These pieces are developing a new voice that I want to use in the next big project I’m planning. A little humorous and wistful. I’ve been waiting for that voice for a long time… Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLike