Friday morning. I’m eating oatmeal for breakfast and reading my morning email. Richard Rohr again, this time a meditation containing a quote from Stephan Harding, Head of Holistic Science at Schumacher College in the UK. “The Work That Reconnects is conceptualized as a spiral that maps the journey to Gaian consciousness [or deep connection with the living Earth] in four stages.”

I know that phrase, The Work That Reconnects. A couple of months back I read a book by Joanna Macy: Active Hope. The subtitle attracted me: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy. That’s where I came across Business As Usual, The Great Unraveling, and The Great Turning. Since finishing that book I’ve been meaning to dive more deeply into the content of those axioms.

Though I’m currently sitting comfortably in Paul’s trailer, working my way through a bowl of Quaker Oats, I’m reminded of what is going on outside—climate change, mass extinctions, economic disruption, all topped off with a pandemic and three and a half million deaths due to the virus worldwide. It’s all right there in the Harding quote about the four stages:

The first is gratitude, in which we experience our love for life. Next is honoring our pain, in which we learn how to suffer the pain of the world with others and with the world itself. Then, in seeing with new eyes, we experience our connection with life in all its forms through all the ages. Finally, in the last stage we go forth into action in the world as open human beings, aware of our mutual belonging in the web of life, learning through feedback in our social and ecological domains.

“Are you ready to head out?” Paul interrupts my musing. “There’s rain coming.” I nod, wash out my breakfast bowl, and drink the last of my morning coffee.

We head south on 101 again—not as far as yesterday. Before crossing over the Chetco River we turn left. These roads east of town all have multiple names: the North Bank Chetco River Road is also County Road 784 and becomes a National Forest road—NF-1376. We pass by Azalea Park, several RV resorts, a rock quarry, a small grocery store, and several neighborhoods of unobtrusive homes similar to those we observed the previous morning. We cross to the river’s south bank a quarter mile past Alfred A. Loeb State Park—closed to camping because of Covid-19. I make a mental note to check it out another time as it looks like a pleasant place to stay for a couple of nights alongside the Chetco.

At Miller Campground the road becomes another dirt track—the national forest road. We haven’t started climbing—we are still in the shade of trees on the wayside. I assume that the drive will be much like yesterday, but as we continue the forest thins out. The landscape changes as the elevation increases, and I realize that a forest fire has swept through here.

I have observed devastation like this but here there is a difference—no new growth. Not a single green sapling emerges from beneath the thousands of scorched dead trees. A ghost forest that no longer breathes, stretches to the horizon, north, south, and east.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” I say out loud. The road keeps rising and the full impact of the waste land becomes numbing.

This is dead ground. Black and grey. The former understory of the forest is a somber ochre brown tinged with pitch-black streaks marking the fire’s route. Dust wafts in the wind. Nothing—nothing at all is alive under a silent grey sky obscured by heavy overcast.

My camera bag is in the car, as it always is, but I haven’t the heart to pull it out and record what I am seeing.

We could continue but there is no point. We’ve reached the high road on the ridge. Mount Emily is behind us. It’s scarred as well. I can see a forest road cutting a conspicuous line on the mountain’s flank. The road in front of us drops back down to the Chetco. I imagine the beauty of the view that has been erased, that I will never see. The river winds east-northeast, a silver trail of reflected light making its way to the Kalmiopsis Wilderness.

“Let’s go back,” says Paul. “I’ve seen this kind of thing before. I don’t want to see it again.” He has traveled and camped extensively in the Western United States, Alaska, and the Southwest throughout his life. It’s difficult to accept the fact that this disaster is some kind of normal. I find a place to turn around and we return the way we came. Once again the mountains fade westwards towards Brookings, but this high ground is naked and fatally wounded.

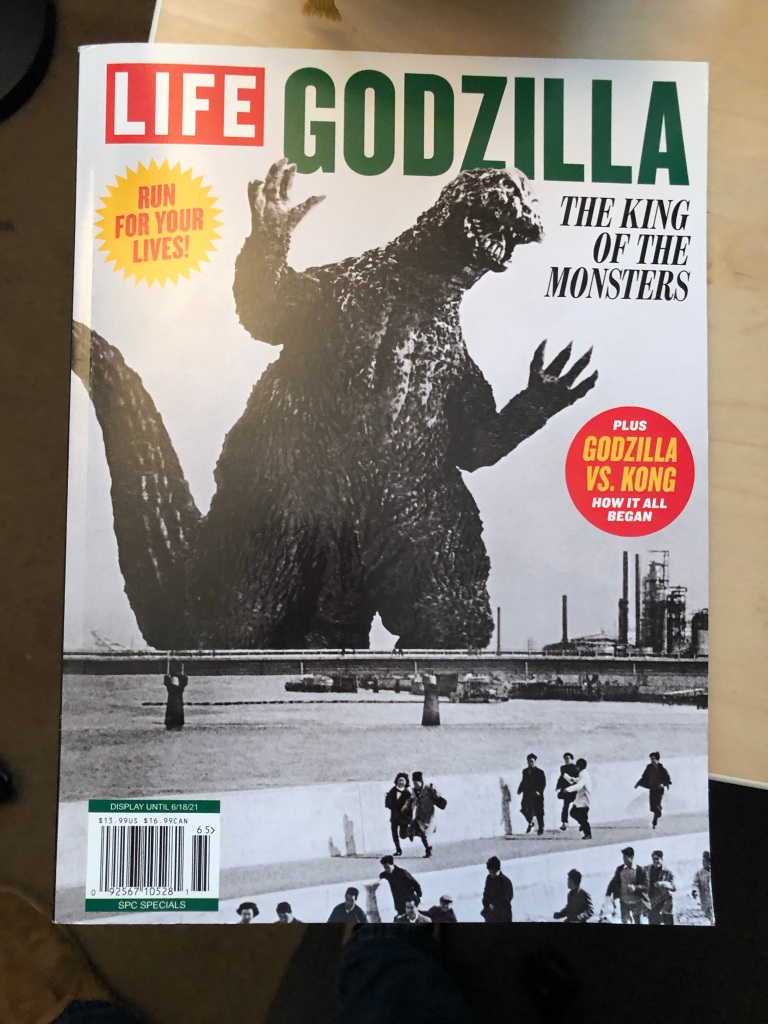

We don’t talk much on the drive back to town. We stop at the Fred Meyer and pick up some ground beef, hamburger buns, and beer. The grocery store is filled with people meandering up and down the narrow aisles. Too many people on the planet, I think. And I’m one of them. As I stand in the checkout line I find a special edition Life magazine about all the Godzilla movies. The sight of it cheers me up and I add it to the grocery basket. My lifelong interest in a make-believe monster that destroys whole cities is sardonic.

I’m thinking that the fire that killed that forest must have come close to ravaging Brookings. I recall from my pre-travel research that a tsunami wrecked the town’s harbor in 2011—a tidal wave caused by an earthquake 50 miles East of Japan’s Oshika Peninsula. I pay for the food, beer, and the glossy biography of a cinematic kaiju, and we return to camp, subdued.

Paul spends time with his iPad researching the fire ands sends me a link to the pertinent Wikipedia article:

The Chetco Bar Fire was a wildfire in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness, Oregon, United States. The fire, which was caused by a lightning strike and first reported on July 12, 2017, burned 191,125 acres (773 km2) as of November 4, when it was declared 100% contained. The Chetco Bar Fire area is subject to warm, dry winds known as the Brookings effect (also known as Chetco Effect), driven by high pressure over the Great Basin.

There it is—the Brookings Effect. The katabatic wind. It plucked the embers from the lightning strike and expanded it to 300 acres by July 20—2907 by August 2—22042 by the 19th. Then the evacuations started, “3 miles up the North Bank Chetco River Road from Social Security Bar to the wilderness retreat area”—exactly where Paul and I had stood. Through the rest of August and all of September and October the fire raged so hot that the fungi and organisms in the soil that nurture the trees were obliterated.

The intended destruction of the Lookout Bombing Raids in 1942 was held in check by the quick-acting observers on Mount Emily. 75 years later random lightning from the sky did the deed, impacting the actual site of the bombing on Wheeler Ridge. The irony here is unsettling, and in the aftermath the Forest Service was criticized for its perceived lack of aggressive response in the initial days of the fire. The official United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) Report to Congressional Requesters states:

Some national forest officials and many stakeholders we interviewed said that the Forest Service was not aggressive enough in fighting the Chetco Bar Fire before the Chetco Effect winds arrived in mid-August. Several of these stakeholders said if the Forest Service had used more aggressive firefighting strategies and tactics, the agency could have prevented the fire from getting as large as it did and threatening homes.

As I read the report back at Harris Beach I wonder why this is a surprise to me. Certainly, a fire of this magnitude is something I would have heard about? I think back to August of 2017 and I remember that I was still living in California—the fire season had started in April and wreaked havoc throughout the state. By October the Atlas, Tubbs, Nuns, and Redwood Valley Complex fires in Napa, Sonoma, Solano, and Mendocino counties had destroyed thousands of structures, including a big section of the city of Santa Rosa, where over 5000 homes were burned out. 44 people died. All of that must have blotted out any reports of the Chetco Fire on the local TV coverage in California.

While the conflagration at the edge of Brookings was being fought and contained, I was witnessing what was happening closer to my Bay Area home. This is from my journal in mid-October:

By the time I got back down to Napa the sun had gone down and the wind had shifted. I stood alongside the Napa River on the western side just a little bit north of the Imola bridge. The hills were burning to the east at the same time as men were fishing from the shore in the safe confines of town. I could hear sirens amidst the sounds of traffic. When I drove through downtown there were people heading out of restaurants and getting on with life. I felt a great sense of loss, a feeling that is becoming familiar to me. So much of what we take for granted is so easily mislaid in a moment.

That journal entry reminds me of what I have forgotten.

The words I read as I ate my oatmeal return to consciousness: “Next is honoring our pain, in which we learn how to suffer the pain of the world with others and with the world itself.”

There is personal pain that arises from the unanticipated events of our own life. There is also the pain of the world, which we try to dismiss, but that is always present. While mulling those truths over in my mind in the fading light of early evening, I walk and return to the view of Bird Island. I stand on the high ground that overlooks the Pacific and the wind blows cold and hard directly into my face, as if to say: wake up, wake up…so much of what we take for granted is so easily mislaid in a moment. The wind uses my own words to remind me that there is something I must do. I don’t know what it is. Some immeasurable certainty is pulsing in the sound of the waves rushing onto the shore, yet this time I am not comforted. By the time I get back to the trailer tiny drops of rain are falling. The weather is changing.

In my uttermost bones I know something, as do you. It is that there can be no despair when you remember why you came to Earth, who you serve, and who sent you here. The good words we say and the good deeds we do are not ours: They are the words and deeds of the One who brought us here.

Clarissa Pinkola Estes

Notes on the text:

- Active Hope – How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy by Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone at Powell’s City of Books

- Wikipedia article on Chetco Fire

- GAO Report regarding the Chetco Fire

- Article from the Siskiyou Crest – The Chetco Bar Fire: Natural Beauty, Industrial Devastation & the Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project. Photographs and maps of the fire.

- Do Not Lose Heart, We Were Made for These Times, article by Clarissa Pinkola Estes, link from dailygood.org

- Kaiju